We should be concerned about our children’s diets. In 2011, nearly 10% of four to five-year-olds in the UK were classified as obese. By the time they leave primary school, nearly 20% of children are obese. Around 40% of these overweight children will continue to have increased weight during adolescence and 75-80% of obese adolescents will become obese adults. If these children are to avoid health problems such as tooth decay, iron deficiency, rickets, type-2 diabetes and heart disease later in life, something has to be done about their diet.

Now that the government has launched a programme of free school meals for all five to seven-year-olds at state school in England, the policy is under the microscope to see if it will actually make a difference to children’s health.

Compared to adults, the energy and nutrient requirements of children are actually relatively similar. Here is a list of six key nutritional elements to be aware of in primary school children.

Now that the government has launched a programme of free school meals for all five to seven-year-olds at state school in England, the policy is under the microscope to see if it will actually make a difference to children’s health.

Compared to adults, the energy and nutrient requirements of children are actually relatively similar. Here is a list of six key nutritional elements to be aware of in primary school children.

Energy

The energy requirement of young children is not far off what we need as an adult. All that physical and mental development needs a lot of energy – as the table shows.

But according to the latest National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS), published in May 2014, children are perhaps getting a bit too much of their daily recommended amounts of certain foodstuffs, as the graph below shows. This could be contributing to obesity. It’s worth noting that the NDNS is a survey, so food intake is often under-reported.

The NDNS also showed intakes of fruit and vegetables were all below recommended levels. Instead of five portions of fruit and veg a day, boys aged between four and ten are eating 3.2 portions, and girls 3.3 portions.

Iron

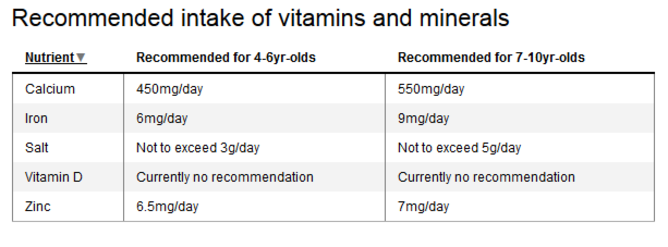

Children also have particular requirements for selected vitamins and minerals to support their rapid growth and development, as the table shows. The NDNS showed that British children aren’t getting enough iron, zinc and calcium. While these have been identified in the new School Food Plan guidance on school nutrition, I am concerned there is no real mention of Vitamin D, a deficiency of which is increasing in frequency.

When it comes to iron, many children do not meet their requirement. This is partly because only 15% of the iron we eat actually gets absorbed. Not having enough iron can lead to tiredness, problems concentrating and poor achievement. Iron also has a role in immunity – particularly helpful with all those bugs flying round the classroom. Rich sources of iron include red meat, eggs and dark green leafy vegetables – not exactly foods that children tend to love. Iron is added to breakfast cereals, which can be a good source. But not all children eat breakfast.

Zinc

According to the NDNS, 9% of children aged four to ten are not getting enough zinc. Needed to support growth, the release of energy from foods and a strong immune system, zinc is vital to child health. Meat, shellfish, dairy, bread and cereals all contain zinc, but if a child’s diet is not varied enough, intake could be limited. As with iron, low levels could contribute to tiredness, lack of concentration and increased risk of recurrent infections.

Calcium and vitamin D

Both calcium and vitamin D have an important role in child development. A deficiency of either could result in rickets, poor growth and an increased risk of osteoporosis later in life. Children obtain most of their calcium requirement from milk, cheese and cereals so it’s not too difficult to get.

Vitamin D is less easy. We get most of our vitamin D from being exposed to the sun yet children spend much of their time indoors. In the summer months we cover them up and plaster on the sun block which significantly reduces their exposure to the ultraviolet rays that are needed for the body to make vitamin D.

In the UK during the months of October, the skin can only make vitamin D between 11am and 3pm, when the sun is strongest. This puts a much heavier reliance on limited dietary sources of vitamin D in the winter, such as oily fish, fortified breakfast cereals, milk and eggs. The NDNS reported children up to three-years-old only managed to achieve 27% of the recommended intake for vitamin D.

Salt

The government’s recommended salt intake for children is 1.8g for four to six-years-old and 3.06g for seven to ten-year-olds, with maximum salt targets between 3-5g. But measuring salt intake is routinely difficult: 75% of the salt children eat is hidden in everyday foods such as breakfast cereals, cheese and bread. In fact cereals are the largest contributor to salt intake (providing around a third of their intake) according to the NDNS.

Both the World Health Organisation and the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence have said adults should be consuming much less salt, but there is no mention of reducing salt targets in children.

Exceeding these salt targets increases the risk of high blood pressure and heart disease later in life. It’s also quite difficult to re-train children’s palates once they get used to highly seasoned, salty foods.

Fibre

Fibre intake in children is often inadequate. Boys aged four to ten are eating around 11.7g per day, while girls are eating 10.8g per day. Many processed foods, particularly those aimed at children, are low in fibre, making constipation a problem. In fact, it’s one of the most common problems in school children today. But too much fibre can fill a child up: if they eat less, they might not get enough nutrient-rich foods to meet their requirements.

Fibre is found in fruit and vegetables, wholegrain breads and cereals. These foods are also rich in vitamins and minerals so make a valuable contribution to a child’s diet. Currently there is no official dietary recommendation for fibre but there are some proposals on the table: the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition released a draft paper on carbohydrates in July 2014. Its proposed recommendations are as follows:

Changing perceptions

At an age when children are developing preferences and independence in terms of food choices, wholegrains and green vegetables have a tough time competing with mass-produced and expertly branded cheesy strings and squeezy yoghurt.

No wonder 25% of five to eight-year-olds think cheese comes from plants, according to the British Nutrition Foundation survey.

Children need better role modelling for healthy eating. If they only see potatoes as long, crispy thin strips and beans smothered in tomato sauce, how on earth can we expect children to know what “real food” is?